Learn more about 16 influential Black writers whose work covers more than 100 years of American history through original works of art created specifically for Dark Testament by contemporary Black artists Bernard Williams, Damon Reed, Dorian Sylvain, and Dorothy Irene Burge.

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was a formerly enslaved person who became a well-known public speaker and author. He honed his oratorical skills as a licensed preacher, and his belief in a Christian God who would deliver freedom gave him hope for his people. Douglass was emboldened by this faith and used his words to transform a world that often refused to recognize his humanity. Eventually, he found his home in Washington, DC, where he continued his activism for racial and social justice.

“What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”

In this speech Douglass charged his white audience to consider what independence meant for enslaved people. His forceful words highlight the hypocrisy of slaveholders celebrating freedom. Douglass closes his speech by reminding his audience that they have the power to bring about change if they are willing to do so.

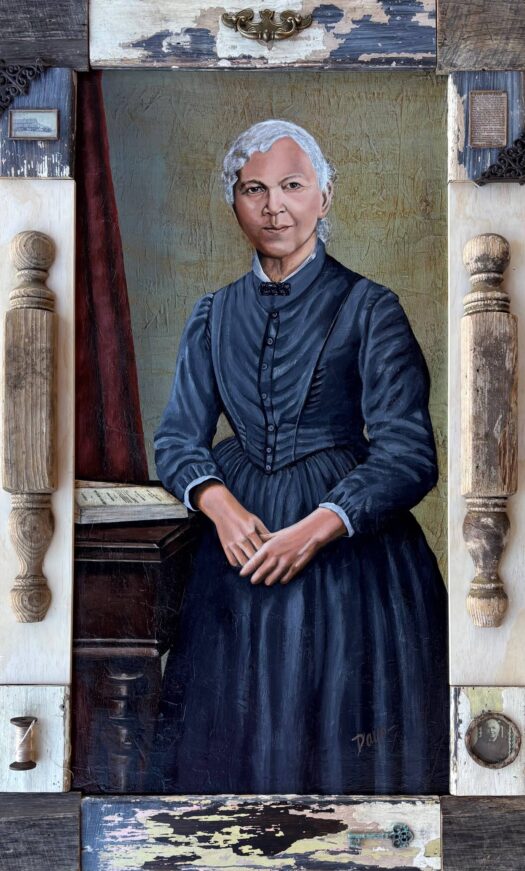

Born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina, Harriet Jacobs (ca. 1813-1897) was the first woman to publish a book-length slave narrative in the United States. Written under the pseudonym Linda Brent, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) recounts her life under slavery and her harrowing escape. She felt obligated to share her firsthand experience and refused to sidestep the issue of sexual exploitation, detailing the relentless harassment by her owner and the ways in which she fought back.

In the summer of 1835, Jacobs ran away from her owner and hid in a crawl space above a storeroom at her grandmother’s house for seven years where she kept busy by sewing, reading the Bible, and writing letters. In 1842, Jacobs escaped to the North and for the next ten years lived as a fugitive slave, dodging attempts by her owner to locate her and eventually landing in Rochester, New York with antislavery activists. Living and working with abolitionists inspired Jacobs to write her autobiography with the hopes of raising awareness of the plight of other enslaved women.

Published just before the start of the Civil War, Incidents was lauded by the abolitionist press but did not garner much attention outside antislavery circles. During the 1860s, Jacobs devoted herself to war relief efforts in the South and assisted former slaves who had become refugees due to the war. Her pastor, the Reverend Francis Grimké, gave her eulogy in 1897 and described her as “the very soul of generosity.”

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was a journalist whose reporting on lynching is still important today. She first discovered her penchant for journalism by writing for a church paper, and would go on to reach a broader readership while still teaching Sunday school, holding ministers to high moral standards, and using churches as community organizing spaces. Her writing condemned anti-Black violence, and she fought for a better future. The Adinkra symbol at the bottom right stands for strength, resourcefulness, and defiance of oppression.

“In lynching, opportunity is not given the Negro to defend himself against the unsupported accusations of white men and women. The word of the accuser is held to be true and the excited bloodthirsty mob demands that the rule of law be reversed…”

Ida B. Wells’ pamphlet documented the rise of white mob violence and the horrors of black lynchings in the southern United States. She found that more than 10,000 Black people had been murdered by lynching, and began a campaign of education to end the carnage.

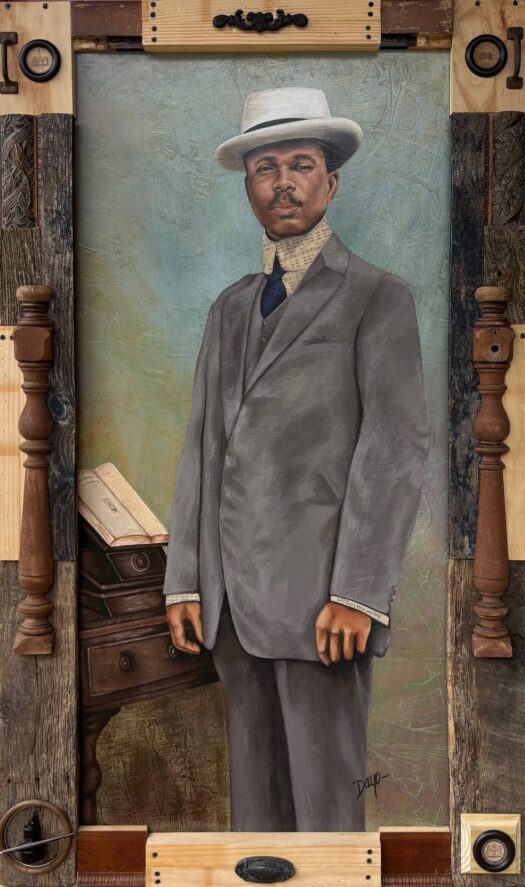

Dayo is a Mixed Media Artist specializing in art that incorporates rescued and salvaged materials from across the country. She’s been saving things from landfills and transforming them into beautiful works of art for over 30 years. She travels to many states exhibiting her work at juried art shows and other events. Her work can also be purchased in The Tennessee State Museum gift shop.

Dayo has had solo exhibits at The Bishop Joseph Johnson Cultural Center at Vanderbilt University and her works can be seen in several centers’ private collections throughout the campus. She has been commissioned as a muralist for Metro Nashville Public Schools and is a self- published illustrator of a children’s coloring book. Her work has been seen on countless online galleries and publications.

Dayo enjoys sharing her gift with people of all ages through teaching private and community based art classes. She currently resides and creates in Nashville Tennessee.

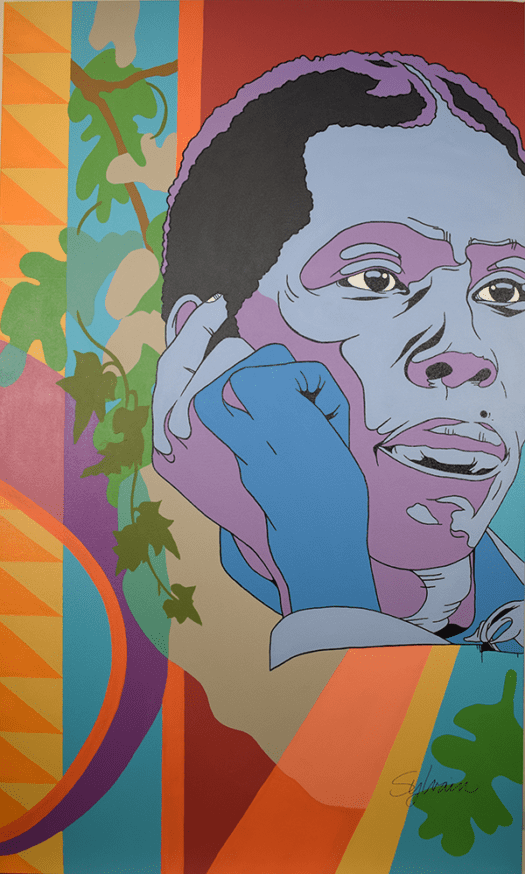

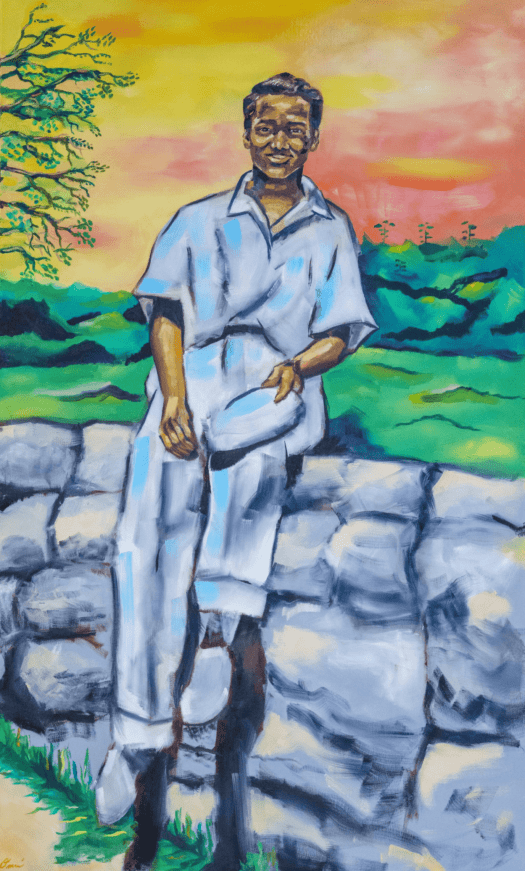

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s (1872-1906) thoughtful gaze would have been well-known to those around him. He became known for writing in the Black dialect of his time. Active during the Post-Reconstruction Era, Dunbar engaged with Christian biblical stories in his fiction during a time when many Black Americans were reimagining the role of religion in their lives. The oak leaves represent his first book of poetry, Oak and Ivy, which contained many poems that discussed racial prejudice.

In high school, Dunbar was already showing promise as a published poet in the Dayton Herald, and an editor for the Dayton Tattler. The Tattler was a short-lived Black paper in Ohio published by Dunbar’s classmate Orville Wright (later known as the co-inventor of the airplane). His poetry only represents a small part of his many novels, short stories, essays, and poems. He was quite prolific for years despite becoming ill, and started to gain wider recognition outside of Ohio, particularly after going on several “reading tours.” He died when he was only 33, leaving behind a literary legacy as one of the foremost Black poets of his day.

Ma Rainey (1886-1939) inspired a generation of Black musicians as the “Songbird of the South.” As one of the earliest blues singers, her music was full of life and soul. Sadly, the importance of her contributions has often been downplayed by historians, and much of her music lost over the years.

Born Gertrude Pridgett, Rainey began her stage career by performing in her parents’ minstrel show. She acquired the nickname “Ma Rainey” through her marriage to William “Pa” Rainey in 1904. Together, the duo toured the South as the “Assassinators of the Blues.” Already a beloved figure in the Southern theater circuit, Ma Rainey became wildly popular during the Blues craze of the 1920s with hits such as “Moonshine Blues” and “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.”

Ma Rainey established herself in the music industry as a prolific songwriter and a shrewd businesswoman, recording nearly a hundred records between 1923-1928. Following her musical career, Ma Rainey returned to her hometown of Columbus, Georgia and was active in the Friendship Baptist Church, where her brother was a deacon, while also owning and operating two theaters of her own. Ma Rainey’s legacy went on to inspire Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, and Alice Walker.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) was a lifelong advocate for abolition and civil rights for Black people and women. She paved the way for women through her writing, speaking, poetry, and activism. In 1859, Harper became the first known African American woman to publish a short story.

Orphaned at age three, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper learned about abolition and advocacy from her aunt and uncle in Baltimore, where her uncle was a minister at the Sharp Street United Methodist Church. Harper’s strong religious foundation informed her work, as she invoked religious themes to advocate for racial justice and wrote in a sermonic style that resonated with Black audiences.

As an adult, Harper traveled to work as a schoolteacher, but was barred from returning to Maryland when the state passed a bill that prohibited free African Americans entry. Unable to return home, she turned her attention to the antislavery movement. Today, Harper is celebrated as a leading antislavery suffragette.

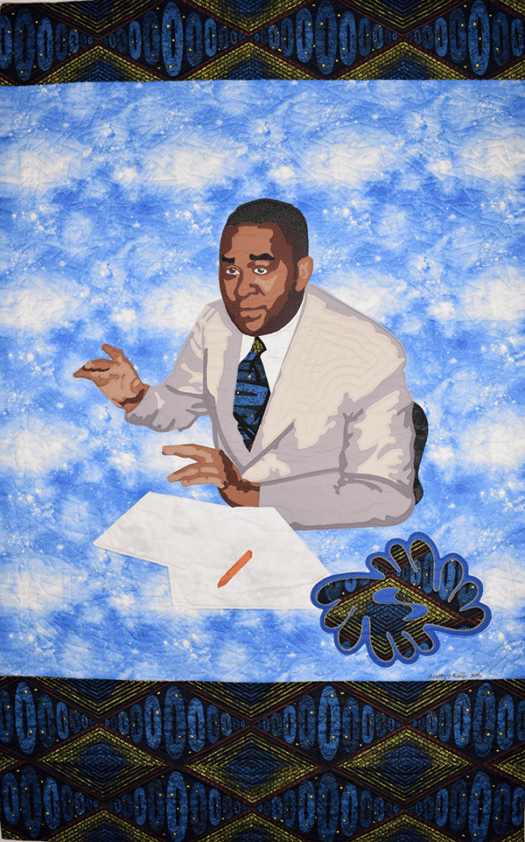

Dorothy Burge is a fabric and multimedia artist and community activist who is inspired by history and current issues of social justice. She is a self-taught quilter who began creating fiber art in the 1990s after the birth of her daughter, Maya.

Dorothy is a native and current resident of Chicago, but is descendent from a long line of quilters who hailed from Mississippi. These ancestors created beautiful quilts from recycled clothing. While she showed no interest in this art form as a child, she grew to treasure the quilts that were created by family elders. Her realization that the history and culture of her people were being passed through generations in this art form inspired her to use this medium as a tool to teach history, raise cultural awareness, and inspire action.

With a white mother and half-sister, Nella Larsen (1891-1964) never felt like she fit in. Her skin was too dark for the immigrant community her mother came from, and too light for the Black community. Through her characters, Larsen illustrated the push and pull of Christianity for Black folks — at once a space to feel free, while also a religion distorted to justify slavery and racism. The hourglass here represents her internal conflict.

Nella Larsen was a brilliant writer who was lost to obscurity for many years after her death. She published 2 novels, Quicksand and Passing, as well as several short stories. In 1930, she was the first Black woman to be awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, but she never published again. Her novels and stories encapsulated her experience as a biracial woman. In addition to her literary career and a brief stint as a librarian, Larsen worked as a nurse for more than 20 years. Today, her work is celebrated and studied in universities across the country.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) used poetry to address racial justice. He was inspired by many things, particularly blues and jazz music, as well as the “rhythms of the Negro church,” as he put it. His writing helped shape the Harlem Renaissance and further solidified a shift away from organized religious practice to a more secular view. For Hughes, this shift is epitomized in blues and jazz, which transcend traditional religion.

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan—

‘Ain’t got nobody in all this world,

Ain’t got nobody but ma self.

I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’

And put ma troubles on the shelf.’

Langston Hughes’ famous poem, “The Weary Blues,” is both a celebration of Black culture and a lament for the hardship faced by Black people. He directly references Harlem in several instances, showing the neighborhood’s importance. Hughes used his narrative voice and the musician’s lyrics to convey a community overwhelmed with problems, but determined to move forward.

Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) studied anthropology in college. Her education and interest in the lives of African Americans laid the foundation for her to write about the depth and breadth of Black experiences. The Adinkra symbol on her dress represents the supremacy of God over all beings. This symbol was chosen in reference to Hurston’s novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Religion played an important role in Hurston’s life and writing. Her father was a Baptist preacher and she enjoyed the excitement and performance of church services, acknowledging its importance as a place for Black folks to make art and be creative. However, she also found the religion she grew up in to be stifling of individual thought and women’s equality. As an adult she used her trained anthropologist’s eye to illuminate other Black folkloric traditions and religious practices by authoring some of the first studies of Voodoo culture in New Orleans, Haiti, and Jamaica.

Sometimes God gits familiar wid us womenfolks too and talks His inside business. He told me how surprised He was ’bout y’all turning out so smart after Him makin’ yuh different; and how surprised y’all is goin’ tuh be if you ever find out you don’t know half as much ’bout us as you think you do.

Zora Neale Hurston wrote this novel, in part, to highlight limitations women face. She examined the intersection of gender, race, religion, and class within Black communities through a series of relationships in the book. Some critics thought that Hurston was promoting stereotypes, which caused a rift with some of her fellow writers.

Born in Phoenix, Arizona, Damon Lamar Reed moved to Chicago in 1996 to attend The School of the Art Institute. After receiving his B.F.A. in 1999, he became a full-time freelance artist making a career out of mural painting, illustration, graphic design, fine art, and teaching. Many of his murals and bricolages can be seen around the Midwest. Damon’s work with various organizations has allowed him to work with young aspiring artists, as well as to perfect his own creative designs. Reed has also built his portfolio to combine music with his visual arts skills.

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) made the case for African Americans to receive full civil rights. Yet, he always felt out of place in the world. When he was in his 90’s, he moved to Accra, Ghana, a country where he felt at home and whose flag is shown here. He became a Ghanaian citizen two years before his death.

Du Bois remained critical of how religion was used to justify slavery and racial domination. By using religious forms in his writing and upending western religious imagery — such as introducing a Black Christ, a Black Madonna, or a Black Buddha — he sought to form a new religious method that would rise above the traditional dogma.

“One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder”

Du Bois wrote The Souls of Black Folk to give voice to the complex experiences of Black Americans. Many were torn between belonging to the Black community and being rejected as Americans by whites. This book was written with a white reader in mind, and spells out the fundamental separation that Du Bois felt.

James Weldon Johnson’s (1871-1938) life defies neat summary. A leader of the Harlem Renaissance, he wrote fiction, poetry, and nonfiction, including an autobiography. He wrote lyrics for many songs, including “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” popularly regarded as the Black National Anthem. He raised public awareness of lynching and fought Jim Crow laws through his activist work with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), of which he was President during the 1920s. Johnson was also a lawyer, diplomat, newspaperman, opera libretto translator, and creative literature professor at Fisk University.

In his anthologies, essays, poetry, and fiction, Johnson celebrated the artistry and diversity of African-American culture—most of it overlooked, misinterpreted, or dismissed by white culture. God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927), the poetry collection many regard as his best, is written in the format of “folk sermons” delivered by “old-time Negro preachers.” Not an ideologue, and more of a freethinker himself, Johnson nonetheless appreciated and celebrated the artistry of Black oratorical tradition.

If there is one unifying thread in Johnson’s work, it is this: in his words and deeds, Johnson conveyed absolute conviction in the limitless creative potential of Black Americans.

Richard Wright (1908-1960) criticized the whitewashed myth of the American Dream, including, as he saw it, an oversized reliance on religious institutions that snuffed out individualism. His protest novel Native Son and his autobiography Black Boy received critical acclaim and showed the challenges poor Black people faced. The Adinkra symbol near Wright’s papers literally means “bite not one another,” which suggests his connection to the Black solidarity movement.

Richard Wright was the grandchild of former enslaved people, and was well acquainted with poverty. He moved from relative to relative as a child, including a time with his grandmother, a Seventh Day Adventist whose strict rules left Wright skeptical of religion. As an adult, he moved from one unskilled job to another until he ended up in Chicago. In 1937, he went to New York where he became the editor of the communist paper Daily Worker. He moved to Paris permanently after World War II.

Dorian Sylvain is a painter whose color and texture explore ornamentation, pattern, and design as identifiers of cultural and historical foundations. She is a studio painter and muralist, as well as an art educator, curator, and community planner. Much of her public work addresses issues of beautification inspired by color palettes and patterns found throughout the African diaspora, particularly architecture. Core to her practice is collaborating with children and communities to elevate neighborhood aesthetics and foster shared understanding.

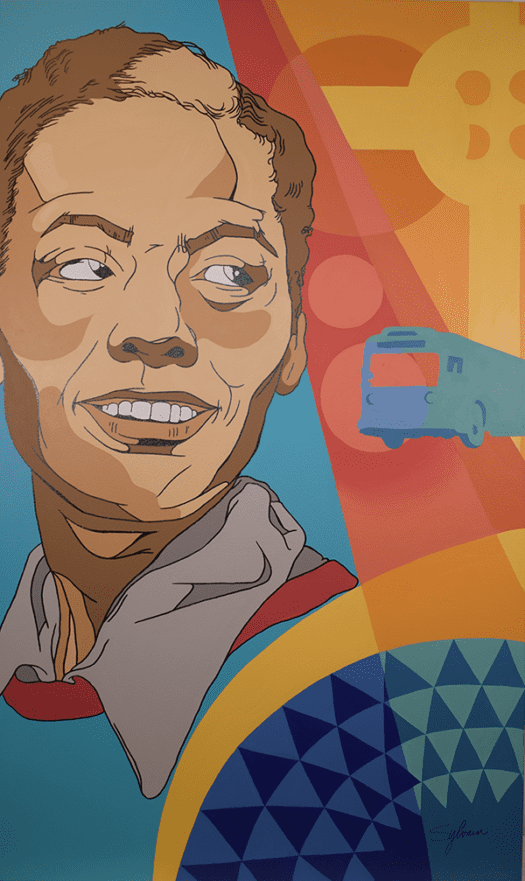

Pauli Murray (1910-1985) was a poet, activist, lawyer, and priest who fought for justice and equality. Murray was an Episcopal Christian her entire life but, due to gender discrimination, often felt like an outsider in her own faith. Eventually, Murray would become the first African American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest. The cross in the background emphasizes her strong commitment to religion, while the bus in the foreground represents her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement.

By 1970, Murray was fighting for women to be allowed to become ordained ministers. She wanted to become a minister herself after caring for a friend, who eventually passed away from a brain tumor. Her first Holy Eucharist as an ordained priest was at the Chapel of the Cross in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. It was the same church her grandmother had been baptized in as a slave. As Murray wrote, “Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female — only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.”

This is our portion, this is our testament,

This is America, dual-brained creature,

One hand thrusting us out to the stars,

One hand shoving us down in the gutter.

The poem “Dark Testament” inspired the name of this exhibit because it exemplifies the complexity of Black life in America. Murray faced violence, struggled with belonging, fought tirelessly for justice, and preached about joy. Their epic poem captures that experience beautifully. The three portraits here represent three stages of Murray’s writing: Poet, Lawyer, Priest.

Visit the online exhibit Pauli Murray: Survival With Dignity

Omari Booker is a multidisciplinary artist based in Nashville, TN and Los Angeles, CA. Oil paintings are Omari’s predominant medium, but mixed media including charcoal, ink, and found objects are essential building blocks of his work, and are used to create finished pieces. Large scale work has been a constant creative outlet for Omari, and murals have also become a consistent part of his creative practice. Storytelling in the form of poetry, prose, and children’s books are also creative outlets.

Omari takes a process-oriented approach to his art, embracing it as a therapeutic modality through which he is able to express his passion for the freedom and independence that the creative process allows him to experience. His art is his personal therapy, and his desire is that those viewing it will have personal experiences of catharsis. The philosophy that undergirds Omari’s work is FREEDOM THROUGH ART and he aspires to create work that communicates to his audience their unique and intrinsic ability to be free.

Ethel Payne (1911-1991) was a fearless reporter who would not back down from contentious social issues. Born in Chicago, Payne’s family regularly attended the African Methodist Episcopal Church across the street from their home. She then graduated from the Chicago Training School for City, Home, and Foreign Missions, a tuition-free college of the Methodist Episcopal Church, with a major in social services and was one of the first female Black graduates. With this background, she would come to be known as the “First Lady of the Black Press” due to her commitment to justice and journalistic excellence.

Payne began writing about the Korean War in her journal around 1950, and was hired by the Chicago Defender after a reporter saw her journals. Using simple and straightforward language, Payne reported on topics ignored by the white press. These issues included the poor treatment of African American troops, General MacArthur’s refusal to desegregate the American military, the abandoned babies of Black soldiers and Japanese mothers, and the Black adoption crisis.

In 1970, Payne was hired by CBS, becoming the first African American woman to be a TV and radio anchor for a national news network. Though her legacy as a journalist has been overlooked up until recently, her writing is coming back into the light.

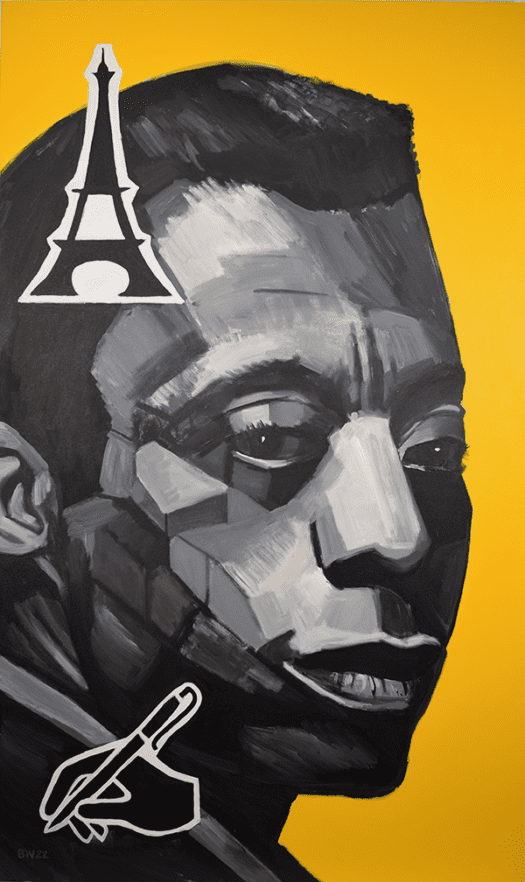

James Baldwin (1924-1987) was a powerful writer and speaker whose words both captured and influenced the long Civil Rights Movement. He grew up in Harlem, New York in a strict religious household, eventually becoming a preacher at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly at the age of fourteen. He broke away from the church a few years later, feeling that religious institutions were hypocritical and insufficient to enact social change. Yet throughout his writing, Baldwin grappled with religion and spirituality, believing that salvation is found in loving one another, not in religious institutions.

After moving to France to finish his novels, he found a sense of belonging there that he didn’t feel in Harlem, New York. Baldwin left for Paris in 1948, beginning a life as a self-styled “transatlantic commuter” who split his time between France and the United States. He launched his literary career with 1953’s semi-autobiographical book Go Tell It on the Mountain.

Baldwin’s passionate discussion of race, gender, sexuality, religion, and class in works such as Giovanni’s Room (1956), Nobody Knows My Name (1961), and The Fire Next Time (1963) were instrumental in shaping the Civil Rights movement. Baldwin made it his mission to “bear witness to the truth.”

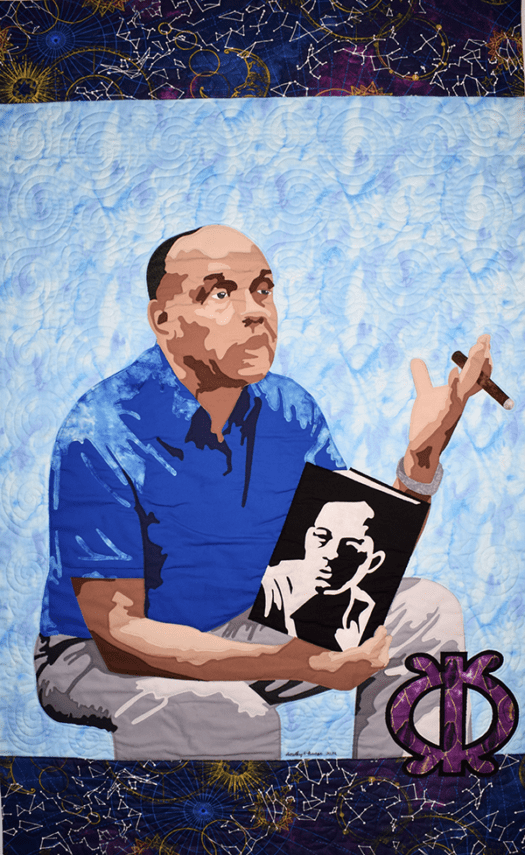

Ralph Ellison (1914-1994) wove together elements of Black culture — music, novels, folklore, philosophy, religion, and history — into his famous novel Invisible Man. He showed the pain of trying to belong in a place that doesn’t see people for anything more than their skin color. The Adinkra symbol near his leg represents toughness in spite of opposition.

Black musical traditions, particularly classic jazz and blues, were of utmost significance to Ellison. He wrote about them in many essays, and incorporated them into his fiction as well. For Ellison, these musical forms constituted a new sort of religion, one that combined aspects of church-based piety with physical expressions of self like song and dance, a merging of the “sacred and profane” that Ellison saw as essential to fulfilling the promises of democracy.

I’m an invisible man and it placed me in a hole—or showed me the hole I was in, if you will—and I reluctantly accepted the fact. What else could I have done?

Invisible Man is considered by many to be a masterpiece of American literature. When it was published, it was met with praise, but also criticism from some of Ellison’s fellow writers. For today’s readers, the novel defines the time in which it was written. Many of its themes continue to speak to the present moment.

Bernard Williams’ studio practice embraces a range of formats for the expression of his interests and concerns. He has created projects which investigate the complexities of American history and culture through painting, sculpture, and installation. Within these broad arenas, the work seeks a kind of open-ended dialogue, addressing identity, flattening hierarchies, and questioning who we are collectively. Risk, adventure, conquest, personal status, privilege, and mechanical development are some of the thematic concepts which are pushed into form.

His works attempt to address our connections and disconnections within a turbulent human history. Not all the signs and images used are clearly identifiable or penetrable.

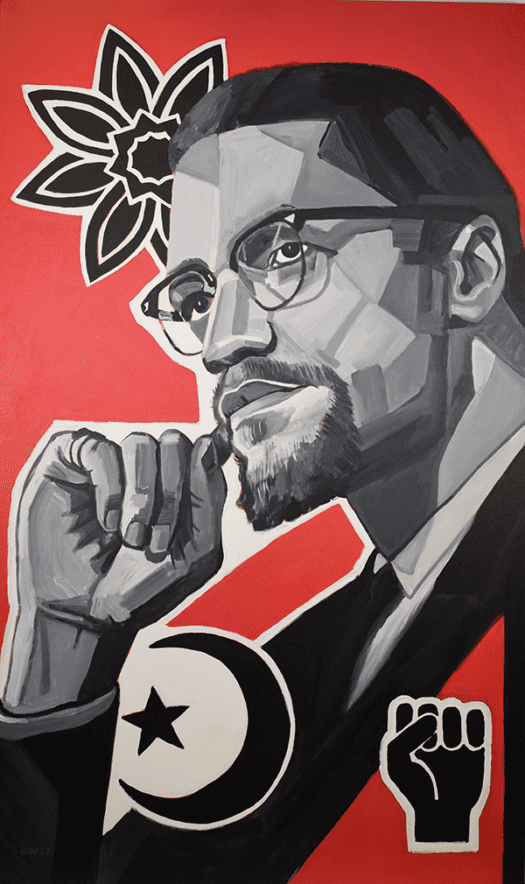

Malcolm X (1925-1965) redefined the Civil Rights Movement as a fight for human rights. He was a member of the Nation of Islam, a black nationalist religious group symbolized by the crescent and star. Malcolm X believed that peaceful protests would not stop acts of violence against people struggling for their rights. He urged his audience to secure their equality by “any means necessary.”

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little in Nebraska. As a child, he lived in foster care for several years before moving in with his older half-sister. As a teenager, he committed several petty crimes and ended up in prison. There, he converted to the Nation of Islam, a combination of the teachings of Islam and Black nationalism. He rose through the ranks quickly and became second in command to Elijah Muhammed.

Between 1955 and 1965, Malcolm came to represent the anger and frustration felt during the Civil Rights Movement. He also was one of the first to use the terms Black or Afro-American instead of Negro or colored. In 1964, he left the Nation of Islam and converted to Sunni Islam. This caused a rift with the Nation, leading to his assassination by Nation member Talmadge Hayer.

Maya Angelou (1928-2014) was a respected spokesperson for Black people and women. Her slight smile and kind eyes convey the joy and beauty she brought to her writing. While her works touch on many difficult themes, the hope she embraced is symbolized by the flying bird. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which cover her childhood and early adult experiences.

In these books, among other events, she relates how her grandmother’s Christian beliefs and teachings influenced her as a young girl, showing her ways to triumph over racism. Angelou also tells the story of appreciating church revival meetings in her youth because Black folks of all religious backgrounds attended them. A plurality of religions would continue to interest Angelou as an adult when she studied Zen Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, and other Christian denominations. Ultimately, she felt most like a Christian and, as she said in an interview with Oprah, “That’s why I am who I am, yes, because God loves me and I’m amazed at it. I’m grateful for it.”

Before becoming a writer, Angelou worked many odd jobs, including as a fry cook, sex worker, nightclub performer, actress, and foreign correspondent. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which tells some of those stories, brought her international recognition. Following its publication, she became a well-known spokesperson for Black people and women, and is widely seen as a defender of Black culture. Angelou was active in the Civil Rights Movement and worked actively with both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Today, her works are widely used in schools and universities worldwide, although attempts have been made to ban her books from some US libraries.

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, poet Nikki Giovanni (1943-2024) was one of the leading voices of the Black Arts movement. Between 1967 and 1970, Giovanni soared to fame with the publication of three volumes of poetry that were popular with Black audiences: Black Feeling, Black Talk (1967), Black Judgment (1968), and Re: Creation (1970). Her work resonated due to its accessible language, personal intimacy, and revolutionary tone aimed at taking down white America.

Giovanni was first attuned to the problems of racism by her grandmother, who worked to support the Black community as a member of the Gospel Church. While in high school, she found inspiration in the work of other Black writers, particularly Gwendolyn Brooks. Giovanni then attended Fisk University, where she studied history and led the reestablishment of Fisk’s chapter of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee. She would continue this commitment to organizing as an adult, working with prominent members of the Black Arts and Black Power movements.

Giovanni wrote prolifically and promoted her work tirelessly, delivering speeches and reading poetry across the nation. She also recorded herself reading her verse over musical tracks, claiming that, in the Black tradition, poetry cannot not be separated from music. The first of these recordings was called Truth Is on Its Way (1971), in which Giovanni was backed by the New York Community Choir.