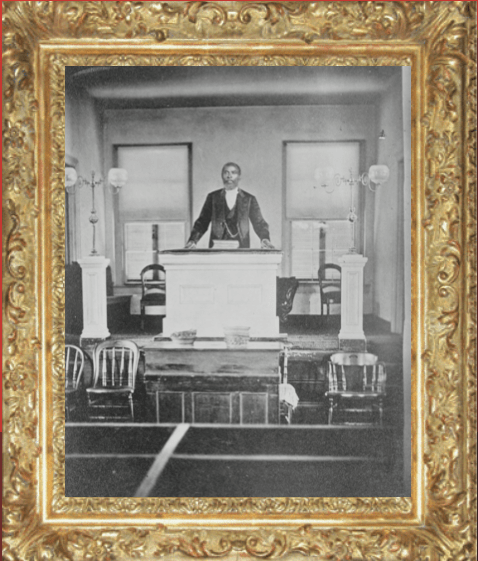

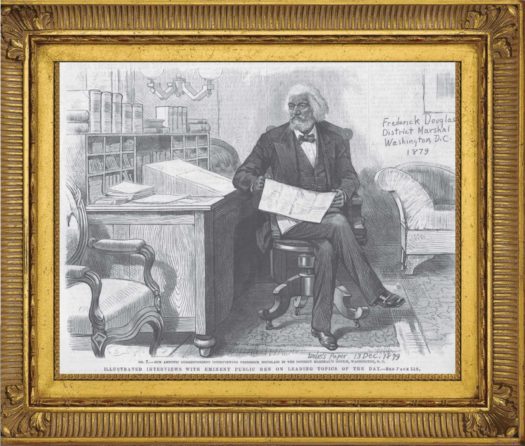

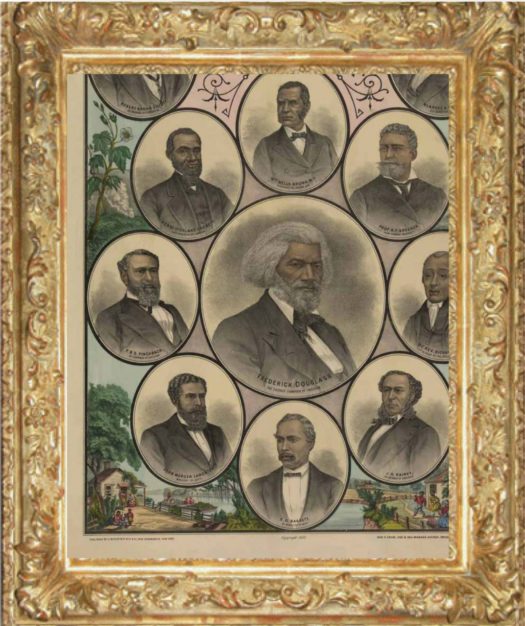

From the end of the Civil War until his passing in 1895 Douglass continued his public speaking with more than 800 speeches. He also wrote all the time, published his newspaper, and served in various government positions for more than 30 years.

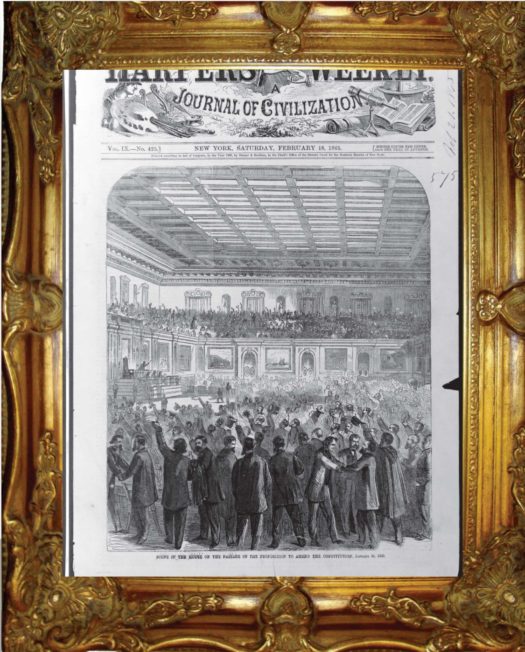

Douglass was a strong supporter of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which outlawed slavery, granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” and gave African-American men the right to vote.

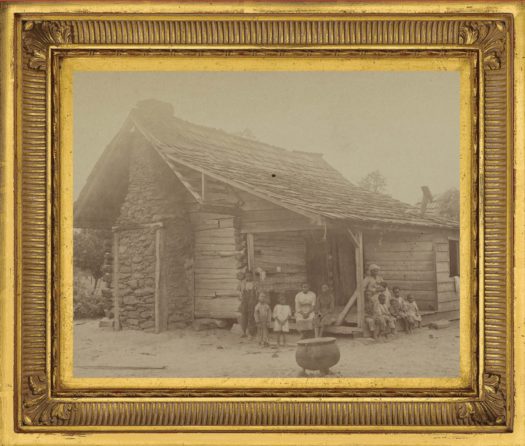

At the same time, Douglass had grave concerns about entrenched racism in the South. He feared that slavery had ended in name only.

“In what skin will that old snake come forth?”

By January 31 of 1865, the Senate and House had passed the 13th Amendment. As the World waited to see if enough states would ratify the law, Douglass emphasized that emancipation could not be the only goal. He felt that the right to vote is essential to citizenship and called for future amendments.

Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot. While the legislatures of the south retain the right to pass laws making any discrimination between black and white, slavery still lives there.

Reconstruction

In this essay, Douglass argues for giving African-Americans the right to vote, calling “the elective franchise” a protective “wall of fire.”

Without a federal law, Douglass worried that southern states would pass their own laws redefining and restricting citizenship. African-Americans would be as powerless as they were before the war.

Get the full speech from the Atlantic

Educational Materials

Resources in conjunction with this exhibit are available to increase your educational experience.

As a slave, what did Frederick Douglass exchange for lessons and knowledge?

Find Out Now!Because Douglass was a slave, he wasn’t allowed to learn to read or write. A wife of a Baltimore slave owner did teach him the alphabet when he was around 12, but she stopped after her husband interfered. Young Douglass took matters into his own hands, cleverly fitting in a reading lesson whenever he was on the street running errands for his owner. As he detailed in his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, he’d carry a book with him while out and about and trade small pieces of bread to the white kids in his neighborhood, asking them to help him learn to read the book in exchange.

(source: Mental Floss)

“An Appeal to Congress for Impartial Suffrage”

The summer before this essay was published, Congress had passed the 14th Amendment, which granted African-Americans the rights of citizenship. Yet, as Douglass explains, citizenship has no meaning without the right to vote.

He details practical and moral reasons for giving African Americans the right to vote, chief among them being a unified North and South.

“[Congress] must enfranchise the negro, and by means of the loyal negroes and the loyal white men of the South build till a national party there, and in time bridge the chasm between North and South, so that our country may have a common liberty and a common civilization. The new wine must be put into bottles. The lamb may not be trusted with the wolf. Loyalty is hardly safe with traitors.”

Hear the full speech from The Atlantic

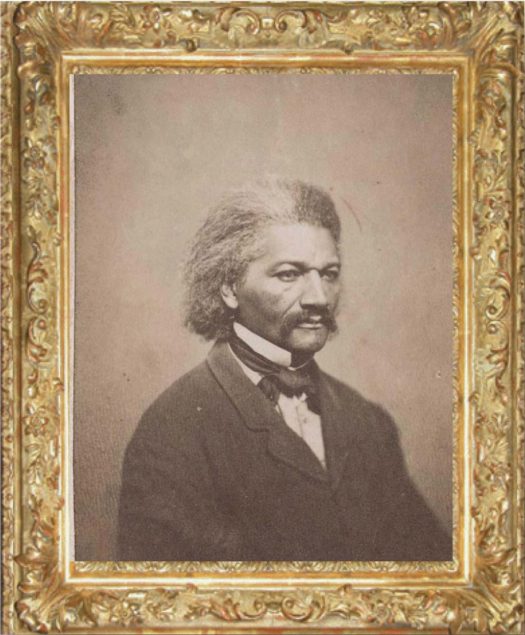

Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

“Seeming and Real”

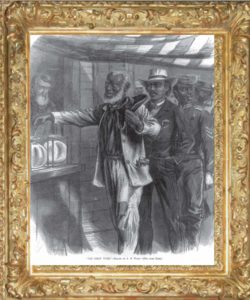

The 15th Amendment, ratified on February 3, 1870, established that the voting rights of U.S. citizens “shall not be denied or abridged…on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Douglass had been fighting for voting rights, but he saw challenges ahead. As he predicted, racism would stop implementation of the law.

“‘There are no colored people in this country’ said a highly poetic friend of ours, not long since. To his mind the fifteenth amendment was not merely a law but a miracle, for nothing less than a miracle could thus so suddenly change black into white, and obliterate all traces of two hundred and fifty years of slavery, both on the part of the race enslaved and the race enslaving. This delirium of enthusiasm is very pleasant to those possessed by it, and it would seem unamiable to disturb it if it did not sometimes stand directly in the way of needed effort.”

As Douglass thought, many states found ways to stop African-Americans from voting long after the 15th Amendment was passed. Tactics included literacy tests, “poll taxes,” and plain bullying. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 tried to get rid of such barriers, and the number of registered African-American voters nationwide jumped from 1 in 4 to almost 3 in 4 today.

Douglass’ definition of equality went beyond the right of African-American men to vote. He believed that women should be able to vote and participate in all levels of government. He advocated for integrated schools. He also supported free speech, a right he often exercised in critiquing the nation’s lawmakers.

“Equal Rights For All”

Douglass was a feminist long before that term even existed. He was the only African-American (and one of only 40 men) at the trailblazing Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. Throughout his career, he delivered many speeches and wrote many essays arguing that women should receive the same rights as men.

“No man should be excluded from the Government on the basis of his color, no woman on account of her sex; there should be no shoulder that does not bear its burden of the Government, and no individual conscience debarred of [a] chance to exercise its influence for good on the National councils.”

“Liberty of Speech [in the] South”

Essay published in the “New National Era”

In 1860, Douglass offered a “plea” for free speech. In his view, suppressing it is a “double wrong” since it “violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.” He returned to the subject in this 1871 essay, calling for freedom of speech in the South.

“Until a man can express his opinion upon all possible subjects as freely and as safely at the South as he does at the North, freedom is the merest farce, and reconstruction a failure. All the rights possessed by citizens of one State must be freely enjoyed in every State.”

“Mixed Schools”

Douglass was an early supporter of desegregating public schools. His logic here is that African-American and poor white communities needed to recognize their “common cause against the rich land-holders of the South.”

He explains that both are “tools” of the rich, in which the rich stir up racist fears to incite poor whites to “in every conceivable manner mistreat” African-Americans.

Explore the later life of Frederick Douglass with curriculum designed for children in grades 1-12

“Looking the Republican Party Squarely in the Face”

Douglass was asked to speak on the opening day of the convention. He begins his speech with grand flourishes of compliments (“I must say … that you are pretty good-looking men”) and thanks them for emancipation and the right to vote.

Then he switches gears stealthily, lethally; he bluntly reminds Republicans that if they don’t protect African-American rights, African-Americans can vote them out of power.

In the 1880s and 90s, violence against African-Americans in the South surged as their civil rights weakened due to restrictive “Jim Crow” laws. At times, it seemed to Douglass that slavery was lifted in name only.

Yet he held out hope that America would eventually live up to its lofty ideals – the “Star-Spangled Banner” was still a favorite tune to play on his violin.

“Our Destiny is Largely in Our Own Hands”

Douglass felt renewed hope in 1883, despite the Supreme Court’s partial overturn of the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Perhaps the fact that African-Americans had been free for 20 years–a whole generation–reminded him that progress had been made. As he wrote in a different essay, “I see colored people steadily rising.”

“Assimilation and not isolation is our true policy and our natural destiny. Unification for us is life: separation is death…All the political, social and literary forces around us tend to unification. I am more inclined to accept this solution because I have seen the steps already taken in that direction. The American people have their prejudices, but they have other qualities as well. They easily adapt themselves to inevitable conditions, and all their tendency is to progress, enlightenment and to the universal.”

“The Future of the Negro”

Given ongoing violence and discrimination, some Americans–black and white–wondered if it made sense for African Americans to stay in the United States. Douglass disagreed.

In this essay, he lists all the reasons why African-Americans would stay, from the practical (it’s expensive to move) to the intangible (things are getting better).

View the full essay on the Library of Congress site

“The expense of removal to a foreign land, the difficult of finding a country where the conditions of existence are more favorable than here, attachment to native land, gradual improvement in moral surroundings, increasing hope for a better future, improvement in character and value by education, impossibility of finding any part of the globe free from the presence of white men,–all conspire to keep the Negro here, and compel him to adjust himself to American civilization.”

Frederick Douglass uses advanced vocabulary in all of his writing.

Can you define these words found throughout the exhibit?

Chasm, Farce, Conspire

Get Definitions!Did you know the definitions? Don’t worry if you didn’t, some of Douglass’ speeches are so complicated you’d need many years of university education just to understand them!

“Strong to Suffer, And Yet Strong to Strive”

The speech finds Douglass weary, contemplating the future of African-Americans in general and wondering aloud about the next generation of civil rights activists. He notes that it is difficult to offer new thoughts on the “same subject, before the same audience.”

He even goes as far as to say that, “I wish that your choice of speaker had fallen upon one of our young men …. I want to see them coming to the front as I am retiring to the rear.” In the speech that follows, he offers advice to those who will follow him.

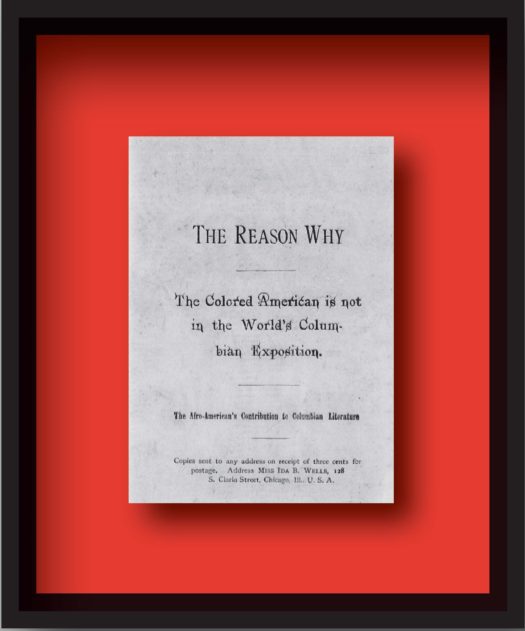

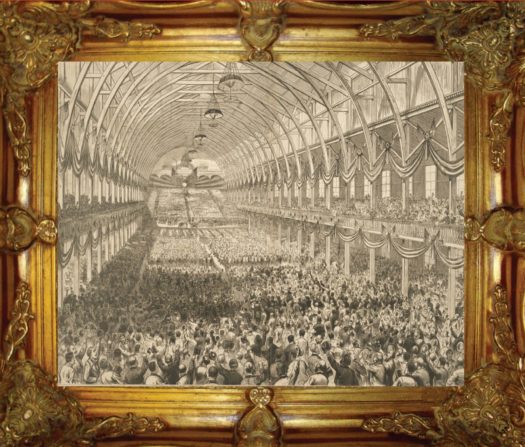

“The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition”

Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 in honor of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to America. The fair took place across 700 acres (that’s about 530 football fields!), and more than 20 million tickets were sold.

Yet, African-Americans could not get jobs at the fair, and were not allowed to create an exhibit showing their culture.

Douglass was one of the few African-Americans at the World’s Columbian Exposition, he served as a representative for the country of Haiti. Angered by the discrimination, he partnered with fellow activist-writers Ida B. Wells, Ferdinand Lee Barnett, and Irvine Garland Penn.

They wrote and distributed this pamphlet together. Douglass would later write a short preface to Wells’ masterpiece about lynching, The Red Record.