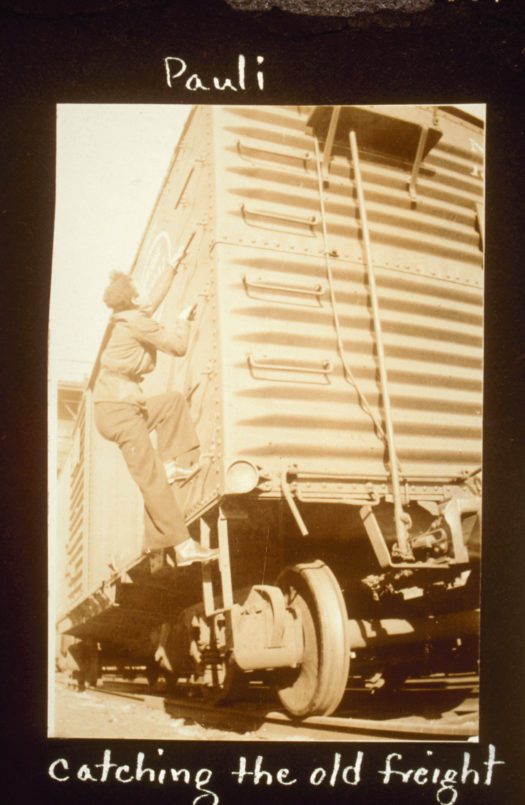

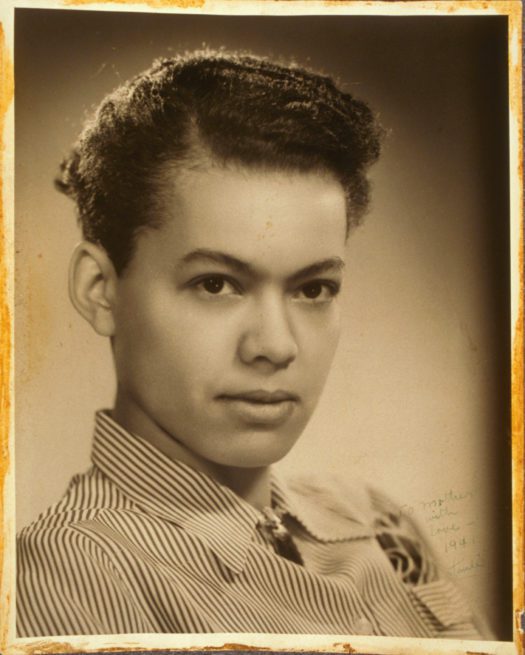

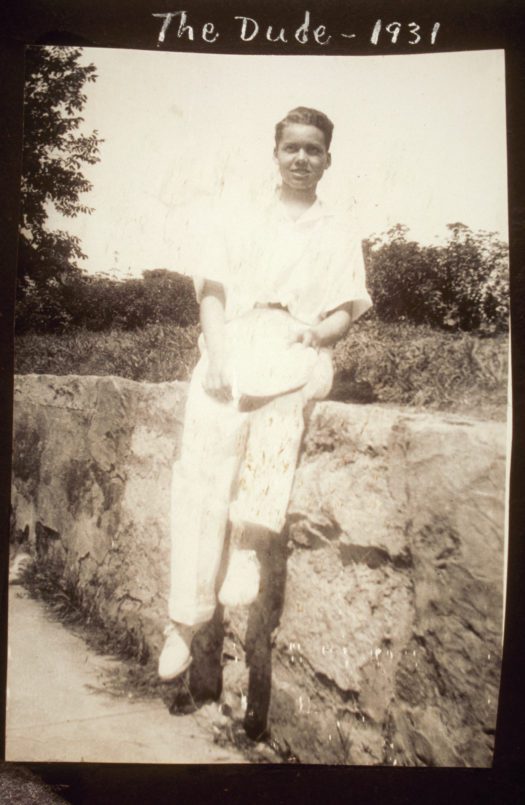

Pauli Murray (1910-1985) was difficult to define. They were a poet, a lawyer, a priest, a freight hopper, Eleanor Roosevelt’s friend, arrested for refusing to comply with bus segregation laws, a closeted member of the LBGTQ+ community, a professor, and so much more. Their work has influenced Supreme Court decisions, the Civil Rights movement, and countless individual people.

In this online exhibit, you may notice that Murray is referred to using both she and they. While she was alive, language and gender expressions were different than they are today. We don’t know what pronouns they might choose to use now. During her lifetime, she wrote with the language available, using she and her. However, throughout their life Murray identified sometimes as a man and sometimes as a woman, which we would now call gender fluidity. Following the example of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, the AWM has chosen to use both she and they to better show the complexity of Murray’s gender identity.

Another term you may notice when reading or listening to Dr. Murray is the word Negro. The AWM has kept Murray’s quotes as close to the original as possible. Murray was a firm believer in the fight to move language from the use of “negro” with a lower-case n to “Negro” with a capital N. They thought that the capital letter showed dignity and respect, and was worried in their later years as language moved to start using “black” instead. This is a great example of the changing nature of language.

Pauli Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1910. She moved in with her aunts and grandparents in North Carolina when she was 3 years old following the death of her mother. Her Aunt Pauline was a teacher, and one of the greatest influences on Murray’s life. She knew from a young age that education was important, and had been denied to her family members because of their race.

As a teenager, Murray moved to New York City to attend Hunter College. The experience opened their eyes to how it felt to be included as opposed to the racial segregation of the South. They went on a trip to California, and while on the road, became inspired to write poetry. They found it to be a powerful way to express their problems, and to fight for change. They loved writing so much that after returning to New York, they were still considering if they could make it a career.

“Color Trouble”

If you dislike me just because

My face has more of sun than yours,

Then, when you see me, turn and run

But do not try to bar the sun.

Murray struggled to decide whether to write full-time, or go to law school. They were drawn to the freedom of writing, as well as the power it gave them. However, at the heart of it, Murray wanted to help people fighting for their liberties. Following a series of events where they were discriminated against for their race repeatedly, Murray knew that the best path was to become a civil rights lawyer. They never stopped writing though, and continued to compose poems the related to their activism as well.

“Harlem Riot, 1943”

Not by hammering the furious word,

Nor bread stamped in the streets,

Nor milk emptied in gutter,

Shall we gain the gates of the city.

But I am a prophet without eyes to see;

I do not know how we shall gain the gates

of the city.

One of the most fitting uses of Pauli Murray’s poetry came in 1968.

What large public event was her poetry read at?

Get the AnswerA verse of “Dark Testament” was read at a public memorial for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Seattle, Washington. There were more than 10,000 people at the service. Many wanted to read the whole poem, and it was re-published with several others in 1970. Reading the verse in honor of one of the greatest fighters for civil rights shows how justice was at the core of all Murray’s work.

Activism drove Murray throughout her life. Fighting for civil rights was a huge part of all of her work, not only as a lawyer, but also as a writer and later as a priest. She fought for justice in multiple ways, but always championed nonviolence. She often wrote about the causes she cared about, particularly by writing letters to those in power.

One of Murray’s first tastes of engaging in activism came when they were applying to the University of North Carolina in 1938. President Franklin D. Roosevelt happened to receive an honorary degree from the university around the same time and gave a speech from the campus. Murray listened to the speech later on the radio. They were surprised by his description of the school as a place that gave opportunities to all young people. Murray knew the school was segregated, so she wrote to the President and his wife, pleading the case of Black people in the South who were often barred from education due to their race.

“Yesterday, you placed your approval on the University of North Carolina as an institution of liberal thought. You spoke of the necessity of change in a body of law to meet the problems of an accelerated era of civilization…. Does it mean that Negro students in the South will be allowed to sit down with white students and study a problem which is fundamental and mutual to both groups? … Or does it mean that everything you said has no meaning for us as Negroes, that again we are to be set aside and passed over for more important problems?”

They were surprised and encouraged to receive a reply from Eleanor Roosevelt. The President’s wife urged them to not push too hard, but keep fighting. The University of North Carolina informed Murray about a month later that they could not attend because they were Black. They contacted the NAACP, starting the work of connecting with leadership that would continue the rest of their life.

Many other incidents followed. In 1940, they were arrested in Virginia for refusing to obey bus segregation laws in the South. While attending Howard University in the 1940s, they were involved in sit-ins. These protests successfully desegregated at least one local diner. The demonstrations also inspired other student sit-ins during the Civil Rights Movement.

As a professor in the 1960s at Brandeis University, Murray was surprised to find themself on the other side of an activist movement. You may notice Murray uses the term Negro/es to refer to Black people. Language changed rapidly in the 1960s, and many phrases we now take for granted started being used. Murray thought that using “black” meant being unsure of who you were. She preferred the capital letter that carried some respect by using Negro. Their students often disagreed on the language, even as they fought for the same causes.

Murray graduated at the top in their class at Howard University. They planned to continue their education to become a lawyer. Traditionally, the top graduate from Howard had been given a fellowship at Harvard Law School, so Murray made plans to enroll there. However, just before graduation they were told that they could not be admitted to Harvard Law because the school did not allow female students.

Gender was a complicated topic for Pauli. They were filled with turmoil about whether they were male rather than female. Rejection based on a sex that they never fully identified with surely stung even more. They fought the decision but were ultimately denied. Harvard Law did not admit women until 1950.

“Counsel”

Beware of body’s fire

Take less than you desire,

Count not tomorrow’s need

With this day’s scattered seed.

Murray attended the University of California, Berkley for her master’s program. She was more determined than ever to make it as a lawyer after the rejection from Harvard. Her final thesis was published in the California Law Review. In 1946 she passed the bar exam and was hired as the state’s first Black deputy attorney general. She went on to become an incredibly influential civil rights lawyer.

The field of civil rights law would not have been the same without Murray’s work. She fought against discrimination her whole life, even while facing the same prejudices at every turn as a queer Black woman. Murray’s name and contributions deserve a higher place in history than they are currently given.

“If one could characterize in a single phrase the contribution of Black women to America, I think it would be ‘survival with dignity against incredible odds’…”

Murray was an Episcopal Christian their entire life. However, due to discrimination within the church based on sex, they often felt like an outsider in their own faith. As an adult, they had mixed feelings about Christianity in general, but always wanted to be more actively involved with the church.

Though she began going to a church that included women more regularly, they were still not present as priests. One day in 1966, Murray had had enough and simply walked out of church during the service. She later wrote a letter to her priest, which included these cutting lines:

“If, as I believe, it is a privilege to assist the priest in the solemn Eucharist, to hold the candles for the reading of the Gospel, to be the lay reader at the formal churchwide 10:30 service, why is this privilege not accorded to all members without regard to sex? Suppose only white people did these things? Or only Negroes? Or only Puerto Ricans? We would see immediately that the Church is guilty of grave discrimination. There is no difference between discrimination because of race and discrimination because of sex. I believe…that if one is wrong, the other is wrong.”

Take our short survey to provide feedback on this exhibit so we can improve our online experience

Murray was not someone who gave up on a cause. They began petitioning for the inclusion of women in a variety of Church offices. Notably, they were not fighting for women to become members of the clergy at that time.

In 1968, Murray attended the 4th Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Uppsala, Sweden. She was there as a resource in the work against racism which the Christian world was beginning to address globally. At that meeting, several women challenged the all-male leadership of the church. This made gains in female representation in the next meeting in 1975. The meeting in Uppsala was the spark Murray needed to light a fire under the cause for religious equality once again.

By 1970, Murray was teaching at Brandeis while fighting for women to be allowed to become ordained ministers. She still did not want to become a minister herself until several years later, when her good friend Renee Barlow passed away from an aggressive brain tumor. Murray felt that the experience of caring for her friend changed her life. She believed she was “called” to complete her life’s purpose by connecting with people through religion.

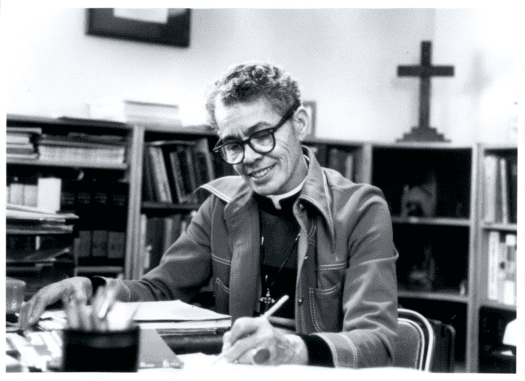

Murray began a three-year seminary course for a Master of Divinity degree in 1973. In 1977, women were finally allowed to be ordained by the Episcopal church. Murray became an ordained priest on January 8, 1977. Their battle against inequality in the church had been won in many ways.

Their first Holy Eucharist as an ordained priest was at the Chapel of the Cross in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. It was the same church her grandmother had been baptized in as a slave, linking together the many battles against oppression they had fought their entire life.

“All the strands of my life had come together. Descendant of slave and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female – only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.”

Explore an interactive map of Dr. Murray’s life

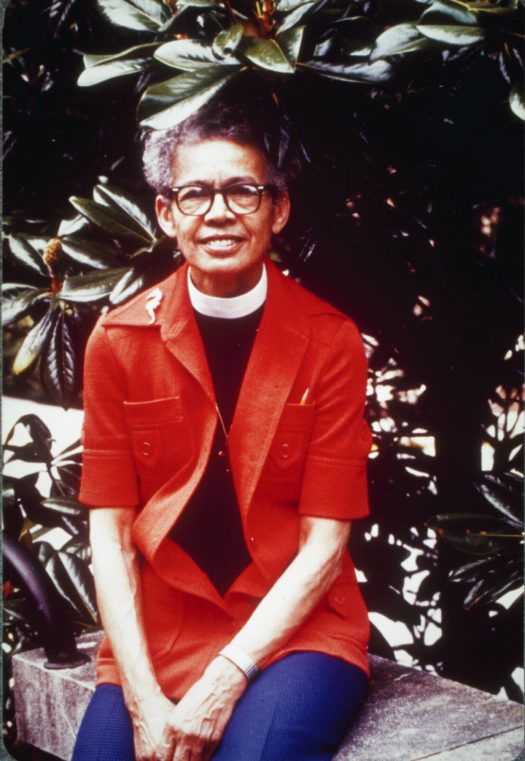

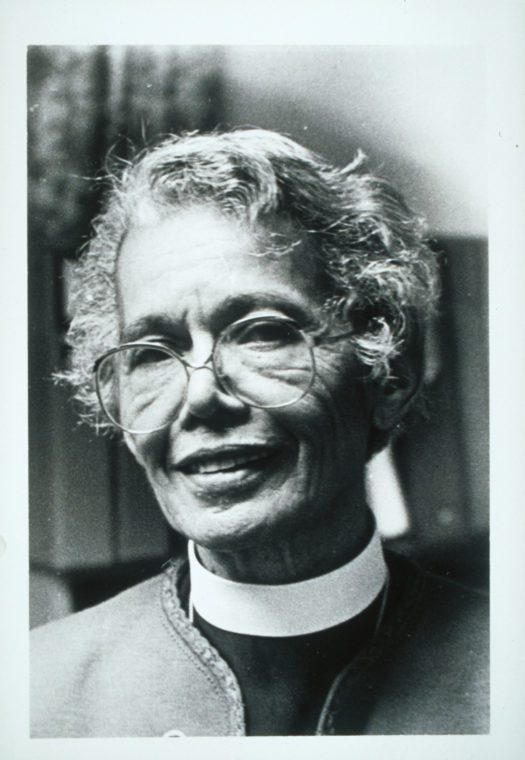

Photo: Murray in their clerical collar in front of a magnolia tree in 1978. © Estate of Pauli Murray, used herein by permission of the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency. Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

Pauli Murray: Survival With Dignity is part of the Dark Testament: A Century of Black Writers on Justice initiative.